Born in San Antonio, Texas, in 1968, Charles Wayne Sexton arrived in Austin at the age of four, with his younger brother (Will Sexton, also a future guitarist) and their mother, and soon found himself immersed in the city’s famous music scene. "[M]y Mom was a huge fan of everything from blues and rockabilly to R & B and rock and roll," Charlie told the Chicago Tribune in 1986. "[S]he'd drag me along to all these shows and clubs."

''[Bob would] just pick up his guitar and start singing and playing without any introduction of explanation--no key, no chords, nothing. And my job was to figure out all the charts and produce it on the spot. We must have cut about 9 or 10 songs, and I`d keep asking him, `Is this one of yours?` and he`d just mumble in this gravelly voice, `Nah, it`s from the Civil War.` With Dylan, you never quite know for sure. They`ll probably all surface on one of his albums about 20 years from now.''

Regrettably, Dylan was right, and Sexton’s decade at MCA was marked by repeated attempts to reinvent him. There was ‘80s Charlie, who released two solo albums and opened for David Bowie on the Glass Spider Tour; early-‘90s Charlie, who formed the supergroup Arc Angels with Doyle Bramhall II and Stevie Ray Vaughn’s rhythm section Double Trouble; and mid-‘90s Charlie, repackaged as a roots-rock singer-songwriter with the 1996 album Under the Wishing Tree (credited to The Charlie Sexton Sextet). All these projects are well worth investigating, but none of them led to the massive breakout success MCA were looking for.

Helen Thompson of Texas Monthly summarised the issue in an article called ‘Little Boy Lost’ in February 1996:

“So what went wrong? Part of the problem seems to have been the nonstop efforts to make Sexton into a star; he was positioned and repositioned so many times that his fans never knew which Charlie they were looking at.”

Charlie’s arrival in the Dylan band prompted a change in the dynamic of a well-established touring group. Whereas it had previously been Dylan and Larry Campbell playing duelling electric guitars - with Bucky Baxter providing colour and texture on pedal steel and other instruments - now Campbell became the multi-instrumentalist, while also forming a formidable guitar partnership with Sexton. Bucky's position as ‘atmospherics man’, however, stayed with Charlie, who fulfilled this role through his subtle yet masterly use of effects pedals, and a unique style that stretched far beyond the bounds of traditional lead or rhythm guitar.

Charlie commented enigmatically on his position in the band during the 2005 No Depression profile. “My role in Bob’s band is between him and me,” he reflected. “He knows what I was there for, and I knew what I was there for.”

Check out this performance of ‘Standing in the Doorway’ to get a sense of what Charlie was doing during this period (you’ll need headphones to get the full effect – Charlie’s guitar is mixed to the right)

Charlie’s influence was also felt strongly on Dylan's 2001 album “Love and Theft”, perhaps most prominently on the closing track ‘Sugar Baby’, on which the eerie sounds coming from Charlie’s guitar deftly shadow Dylan’s vocal. (Charlie's guitar is mixed to the left)

Another favourite of mine from this era is the instrumental break from the 2001-02 performances of ‘Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door’, with Charlie expertly playing around Dylan’s own lead guitar. Charlie never played this break the same way twice, as you can see/hear from the clips below.

Sexton left the Dylan band in November 2002, following that year’s celebrated fall tour. Bob would have a hard time replacing him. In the meantime, Charlie concentrated on building up his resume as a producer - working with artists like Lucinda Williams (on her album Car Wheels on a Gravel Road) - and released his fourth solo album, the Williams-produced Cruel and Gentle Things in 2005, plus a duets album with Shannon McNally called Southside Sessions the following year. He also briefly reformed the Arc Angels with Doyle Bramhall in 2009.

Michael Nave’s review of the concert on Boblinks captured an intriguing post-show interaction between Charlie and Bob:

“Halfway through [the closing song], I moved back to my spot beside the stage where I could view the backstage area as Bob and the band walked down from the stage. As they came down the stairs sure enough Bob and Charlie were walking side by side talking. They walked toward centerfield, then stopped and continued to talk for a few moments, as if they were saying goodbyes; about to part.. But then they continued walking together talking, all the way out of the Dell Diamond. One could only hope the conversation was something like, “sure Bob, I would be glad to do the rest of the Texas dates with you while Stu, Denny, and Donnie take a well deserved few days off. .. .”

Mr Nave’s reading of the situation turned out to be prophetic. By the end of the month, Rolling Stone magazine had announced that Charlie Sexton would be returning to the Bob Dylan band beginning that October. “I love and respect Bob and am very happy to be reunited with my friend onstage,” said Charlie.

For this stint in Dylan’s band, Charlie filled more of a traditional ‘lead guitarist’ role, adapting his playing to suit the blues-rock style Dylan favoured at this time. With Bob mostly on keyboards, Charlie often became the visual focal point of the show, prowling the stage and frequently interacting with Dylan. For a taste of what things looked and sounded like onstage circa fall 2009, have a look at this 'Stuck Inside of Mobile' from that tour:

Things stayed this way from late 2009 to mid-2012. By the end of 2012, however, Charlie’s role had been noticeably reduced, and – although it’s easy to forget looking back – he departed the band once again at the end of the year (one day shy of the 10th anniversary of his first departure). This turned out to be a temporary break: things didn’t work out with Sexton’s replacement, Duke Robillard, and Charlie was back in his old position by the end of the summer 2013 tour.

Charlie was back, but things weren’t going to revert to what they had been in 2009-12. Dylan’s sound was changing, with the rockier style that had dominated most of the preceding decade now replaced with a hushed, delicate sound that brought Bob’s voice and lyrics back to the forefront. In hindsight, this change was more gradual than it initially appeared; it’s already in evidence on much of the 2012 album Tempest, which would serve as the core of Dylan’s live show for much of the 2010s. Charlie’s restrained solo on the track ‘Scarlet Town’ is a good example of what would be required of him over the next few years.

This period segued neatly into Dylan’s extended exploration of The Great American Songbook, which encompassed the albums Shadows in the Night (2015), Fallen Angels (2016), and Triplicate (2017). The band’s playing on Shadows in the Night, in particular, is so subtle that it sometimes sounds like Dylan is backed only by Donnie Herron’s pedal steel. As always, though, Charlie’s playing (mixed to the left) rewards close attention: just listen to how he weaves around and responds to Bob’s vocal on ‘Full Moon and Empty Arms’.

By 2018, Dylan had returned to concentrating on his own material, and was reintroducing songs that had been absent from his show for some time. Charlie Sexton, a 40 year veteran at 50 years old, had by this point acquired the aura of an old master, able to anticipate every sudden left turn that Dylan might take during a song. In 2019, the fall tour contained what might be Charlie’s finest contribution to Dylan’s live show: a stunning reworking of ‘Not Dark Yet’, in which Charlie conjures an atmosphere filled with ghosts and shadows while Bob’s voice floats over it all like mist across a lake. My favourite performance of this arrangement is the one from University Park, Philadelphia - particularly the last verse, where Charlie’s guitar answers Bob’s vocal at the end of each line.

Following that well-received tour, the band reconvened with Bob in early 2020 to record the album that would become Rough and Rowdy Ways, which was released in June. In the interview with Douglas Brinkley that accompanied the album, Dylan – somewhat uncharacteristically – went out of his way to heap praise on his long-serving guitarist:

DB: Charlie Sexton began playing with you for a few years in 1999, and returned to the fold in 2009. What makes him such a special player? It’s as if you can read each other’s minds.

BD: As far as Charlie goes, he can read anybody’s mind. Charlie, though, creates songs and sings them as well, and he can play guitar to beat the band. There aren’t any of my songs that Charlie doesn’t feel part of and he’s always played great with me. “False Prophet” is only one of three 12-bar structural things on this record. Charlie is good on all the songs. He’s not a show-off guitar player, although he can do that if he wants. He’s very restrained in his playing but can be explosive when he wants to be. It’s a classic style of playing. Very old school. He inhabits a song rather than attacking it. He’s always done that with me.

It certainly sounds like Charlie playing the guitar solos on ‘False Prophet’. On most of the record, however, I believe Charlie can be heard shimmering away on the far left-hand side of the mix. It’s hard to describe this incredibly subtle style of playing: the phrase that springs to my mind is ‘sound effects.’ It’s particularly effective on some of the quieter, slower tracks like ‘I Contain Multitudes’, ‘I’ve Made Up My Mind to Give Myself to You’, and ‘Mother of Muses’. Once again, you need headphones to really zero in on what’s going on here.

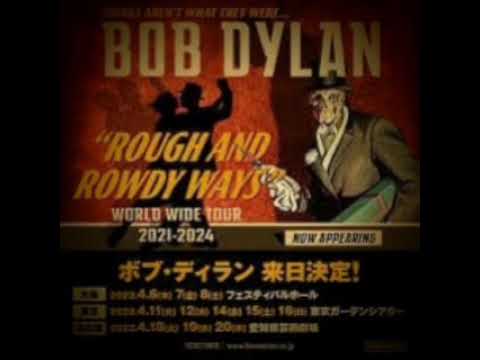

Rough and Rowdy Ways turned out to be Charlie’s last stand to date with Bob. Shortly afterwards, of course, came the Covid-19 pandemic, and once the dust had settled and Dylan was able to resume touring, Charlie had moved on to pastures anew. By this point it had been 22 years since Charlie played his first show as a member of Bob’s band, and 38 years since the two had met for the first time.

If you like Charlie Sexton but wish he played a bouzouki instead of a guitar, then this is the video for you!

I'm not sure what song Charlie is singing in this video from 2017, but his playing is fascinating. As a couple of the comments note, it's very much in the 'desert blues' style prevalent in Mali, West Africa, popularised by the late Ali Farka Toure.

And finally, this:

Sources:

'CHARLIE SEXTON -- SEXY AND 17' by Steve Pond, Los Angeles Times, 18th May 1986

'CHARLIE SEXTON, IN THE BIG TIME AT 17, IS THROWING ALL HIS PASSION INTO WORK' by Iain Blair, Chicago Tribune, 6th April 1986

'Little Boy Lost' by Helen Thompson, Texas Monthly, February 1996

'Charlie Sexton - The Austin Kid' by Don McLeese, No Depression, 1st September 2005

'Charlie Sexton exceeds all expectations' by Kim Curtis, Chron., 3rd November 2005

'Changing hats' by Chris Parker, San Antonio Current, 19th March 2008

Reviews: Round Rock, Texas, The Dell Diamond, 4th August 2009 - BobLinks

'Bob Dylan Welcomes Guitarist Charlie Sexton Back Into His Band', by Andy Greene, Rolling Stone, 26th August 2009

'Charlie Sexton Interview Part I: How to Session with Bob Dylan' by Arlene R. Weiss, Guitar International, 8th August 2011

'Charlie Sexton: Too Many Ways to Fall' by Jason Crouch, 2019

ReplyDeleteI saw a concert where Bob was at the side of the stage with his keyboard, and Charlie was unleashing riffs and twists, taking center stage, in a way that was unusual for the band. Do you know when that was?