“That’s what it is. It’s work. All artistic endeavour requires effort. It requires work. More than anything else – more than inspiration, more than influence, even more than aesthetic. For me, it just requires showing up and doing it. Talk to any painter, any photographer, any sculptor, any musician, any poet, any writer – it’s showing up! If you gotta do the thing, then you gotta do the thing. That’s really what it’s all about.

- Pixies frontman Black Francis, 2019 Guitar.com interview

In November 2016, less than a month before his death, Leonard Cohen held a press conference to celebrate the release of his new album You Want It Darker. When asked about how he had continued to produce high quality material over such a long period of time, Leonard had this to say:

Few people know of the songwriter’s struggle as well as Cohen, who was known to labour over songs for many years before deeming them ready for the world. It’s interesting, though, that he goes out of his way to mention Dylan, who has previously spoken of his own difficulties in keeping his creative engine, as Leonard calls it, “receptive and well oiled”. The topic came up during Dylan’s 2004 interview with the late Ed Bradley on 60 Minutes:

This technique was in evidence when Dylan came to record Time Out of Mind in 1997. Thanks to the release in 2008 of The Bootleg Series Volume 8: Tell Tale Signs, which contains numerous Time Out of Mind outtakes and alternate takes, we can see how various lines and phrases migrated from one song to another. For example:

Dylan’s follow up to Time Out of Mind, 2001’s “Love & Theft”, featured further evidence of the new approach. On the lyrical front, it soon emerged that numerous lines on the album had been taken from Junichi Saga’s 1991 novel Confessions of a Yakuza, while Scott Warmuth has revealed other lyrical appropriations from songs recorded by the New Lost City Ramblers. The musical arrangements were drawn from an even wider array of sources, including Johnny and Jack, Jerry Lee Lewis, Big Joe Turner and Billy Holiday. The album is essentially the musical equivalent of a quilt – second hand material lovingly stitched together to create something new.

The same creative process would be used on Dylan's next album, 2006’s Modern Times (and also in his autobiography, Chronicles - but that really deserves an article of its own). Lyrical sources on the album included Ovid and Civil War-era poet Henry Timrod, while arrangements and/or melodies were drawn from the likes of Muddy Waters, Bing Crosby, and Memphis Minnie and Kansas Joe McCoy. Dylan changed tack for the following album, 2009's Together Through Life, co-writing the lyrics with the Grateful Dead’s Robert Hunter, but the album still included some borrowed arrangements, one of which – the arrangement of Muddy Waters’ ‘I Just Want to Make Love to You’, which was used for ‘My Wife’s Home Town’ - was acknowledged in the album credits. Tempest (2012) featured arrangements and melodies derived from a range of artists including Bobby Fuller Four, The Greenbriar Boys, and The Carter Family, while several phrases in ‘Scarlet Town’ have been found to originate from the work of 19th Century poet John Greenleaf Whittier.

“I think that any songwriter, and I think that Bob Dylan knows this more than all of us … you don’t write the songs anyhow. If you’re lucky, you can keep the vehicle healthy and responsive over the years; if you’re lucky, your own intentions have very little to do with this. You can keep the body as receptive and well-oiled as possible, but whether you’re actually going to be able to go for the long haul is really not your own choice.”

Few people know of the songwriter’s struggle as well as Cohen, who was known to labour over songs for many years before deeming them ready for the world. It’s interesting, though, that he goes out of his way to mention Dylan, who has previously spoken of his own difficulties in keeping his creative engine, as Leonard calls it, “receptive and well oiled”. The topic came up during Dylan’s 2004 interview with the late Ed Bradley on 60 Minutes:

Bradley: Do you ever look at music that you’ve written, and look back at it and say ‘whoa, that surprised me’?Dylan: I used to. I don’t do that anymore. I don’t know how I got to write those songs.Bradley: What do you mean you don’t know how?Dylan: Well, those early songs were almost like magically written. [quotes the first verse of ‘It’s Alright Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)’] Well, try to sit down and write something like that. There’s a magic to that, and it’s not Siegfried & Roy type of magic. It’s a different kind of a penetrating magic, and I did it at one time.Bradley: You don’t think you can do it today?Dylan: [shakes head]Bradley: Does that disappoint you?Dylan: Well, you can’t do something forever, and I did it once. I can do other things now, but I can’t do that.

It’s very common for an artist’s creative process to change over time; Cohen, for example, often worked with collaborators like Sharon Robinson and Patrick Leonard to set his lyrics to music in later years. Bob Dylan’s solution to his changing relationship with his muse was somewhat different: as he entered the 21st Century, Dylan began constructing songs from a variety of existing sources, using old songs from the ‘30s, ‘40s and ‘50s as the basis for his arrangements, and applying a variant of the ‘cut-up technique’ for his lyrics, often using phrases from existing texts. While there has always been a ‘borrowing’ element to Dylan’s work, this was something different.

Dylan has been aware of the cut-up technique since at least 1965. Incredibly, Don’t Look Back director D.A. Pennebaker actually captured footage of him explaining the concept at length that very year, and revealing that an attempt to use it for one of his songs “didn’t work out”. Bob used a variation of the method to edit his films Eat The Document and Renaldo and Clara, and appears to have tried out the technique again for his 1985 album Empire Burlesque, which featured a surprising number of lines from Humphrey Bogart films. However, he seems to have only truly committed himself to the practice in the 1990s, as director Larry Charles discovered when he entered talks with Bob to create a slapstick comedy TV series with Dylan in the lead role (which later evolved into the 2003 film Masked & Anonymous). As Charles recalled in an interview on Pete Holmes’ You Made It Weird podcast in 2014:

“He brings out this very ornate beautiful box, like a sorcerer would, and he opens the box and dumps all these pieces of scrap paper on the table … Every piece of paper was hotel stationary, little scraps from, like, Norway and Belgium and Brazil, and each little piece of paper had a line. Some kind of little line, or a name, scribbled - “Uncle Sweetheart” - or a weird poetic line, or an idea… I realised: that’s how he writes songs. He takes these scraps and puts them together, and makes this poetry out of that.

This technique was in evidence when Dylan came to record Time Out of Mind in 1997. Thanks to the release in 2008 of The Bootleg Series Volume 8: Tell Tale Signs, which contains numerous Time Out of Mind outtakes and alternate takes, we can see how various lines and phrases migrated from one song to another. For example:

* The outtake ‘Marchin’ to the City’ - which the liner notes tell us gradually evolved into ‘’Til I Fell in Love with You’ - contains the lines “Looking for nothing in anyone’s eyes” and “Go over to London/Maybe gay Paree/Follow the river/You get to the sea”, both of which ended up in ‘Not Dark Yet’ in a slightly reworked form.* The early version of ‘Can’t Wait’ features the phrase “Think you’ve lost it all, there’s always more to lose”, which found its way into ‘Tryin’ to Get to Heaven’ as “When you think that you’ve lost everything/You find out you can always lose a little more”. As is noted in the liner notes, the song also contains the lines “My back is to the sun because the light is too intense/I can see what everybody in the world is up against” which became the opening lines of ‘Sugar Baby’ on “Love & Theft”.* A large portion of the lyrics from the outtake ‘Dreamin’ of You’ were included in ‘Standing in the Doorway’, although one line (“Feel further away than I ever did before”) turns up slightly rephrased in ‘Highlands’.* The research of Scott Warmuth has also revealed that a number of phrases on the album are derived from the work of Henry Rollins.

Why did Dylan adopt this method? The most likely answer is, as Leonard Cohen said, that “you don’t write the songs anyhow”. Creativity is often hard work, a grind, and genuine inspiration is too rare to be relied upon. In a 1978 interview with Matt Damsker, Dylan had spoken of learning to do “consciously what I used to do unconsciously” in his songwriting, and the creative process he leaned into in the 21st Century could be seen as an extension of that mindset.

Dylan’s follow up to Time Out of Mind, 2001’s “Love & Theft”, featured further evidence of the new approach. On the lyrical front, it soon emerged that numerous lines on the album had been taken from Junichi Saga’s 1991 novel Confessions of a Yakuza, while Scott Warmuth has revealed other lyrical appropriations from songs recorded by the New Lost City Ramblers. The musical arrangements were drawn from an even wider array of sources, including Johnny and Jack, Jerry Lee Lewis, Big Joe Turner and Billy Holiday. The album is essentially the musical equivalent of a quilt – second hand material lovingly stitched together to create something new.

The same creative process would be used on Dylan's next album, 2006’s Modern Times (and also in his autobiography, Chronicles - but that really deserves an article of its own). Lyrical sources on the album included Ovid and Civil War-era poet Henry Timrod, while arrangements and/or melodies were drawn from the likes of Muddy Waters, Bing Crosby, and Memphis Minnie and Kansas Joe McCoy. Dylan changed tack for the following album, 2009's Together Through Life, co-writing the lyrics with the Grateful Dead’s Robert Hunter, but the album still included some borrowed arrangements, one of which – the arrangement of Muddy Waters’ ‘I Just Want to Make Love to You’, which was used for ‘My Wife’s Home Town’ - was acknowledged in the album credits. Tempest (2012) featured arrangements and melodies derived from a range of artists including Bobby Fuller Four, The Greenbriar Boys, and The Carter Family, while several phrases in ‘Scarlet Town’ have been found to originate from the work of 19th Century poet John Greenleaf Whittier.

*

One of the most interesting aspects of the 60 Minutes interview is Dylan’s visible disappointment about how his relationship with his creativity has changed since the 1960s. It’s rare for him to touch on the subject publicly; while Bob has been quizzed about his borrowing of lyrical material, he has never (as far as I can tell) been asked about his reasons for doing so. On the other hand, perhaps the best place to look for the answer to that question is within the songs themselves.

‘Ain’t Talkin’’, the final song on Modern Times, is a song I have always found rather elusive; until recently, it never quite grabbed me in the same way that many Bob Dylan album closers have. However, a close examination reveals that there’s a lot going on in the lyrics, many of which seem to relate to the narrator’s loss of his former powers. Take the seventh verse, for example:

One of the most interesting aspects of the 60 Minutes interview is Dylan’s visible disappointment about how his relationship with his creativity has changed since the 1960s. It’s rare for him to touch on the subject publicly; while Bob has been quizzed about his borrowing of lyrical material, he has never (as far as I can tell) been asked about his reasons for doing so. On the other hand, perhaps the best place to look for the answer to that question is within the songs themselves.

‘Ain’t Talkin’’, the final song on Modern Times, is a song I have always found rather elusive; until recently, it never quite grabbed me in the same way that many Bob Dylan album closers have. However, a close examination reveals that there’s a lot going on in the lyrics, many of which seem to relate to the narrator’s loss of his former powers. Take the seventh verse, for example:

Well, it's bright in the heavens and the wheels are flyin'Fame and honor never seem to fadeThe fire gone out but the light is never dyin'Who says I can't get heavenly aid?

The narrator seems to be saying that although his powers have diminished, no one has noticed, and, through the grace of God, he still enjoys the same “fame and honor” that he did in his earlier years. It’s certainly true that Dylan had enjoyed commercial and critical acclaim from Time Out of Mind onwards, with most reviewers and the public either unaware or unconcerned with the second-hand nature of some of the material.

Other phrases jump out: lines like “My eyes are filled with tears, my lips are dry”, “my mule is sick, my horse is blind” and “They will tear your mind away from contemplation” hint at writer’s block, while “Carryin’ a dead man’s shield” and “There’s no one here, the gardener is gone” almost sound like an admission of imposter syndrome. And then there’s the song’s eerie refrain: “Ain’t talkin’, just walking”. Maybe that’s what Bob felt he was doing at this point in time, traversing the globe on his Never Ending Tour but unable to connect with his muse in the way he once had. It’s a desperately sad song, but the closing major chord, which ends the minor-key song on an unexpectedly upbeat note, perhaps offered a sign that all was not lost.

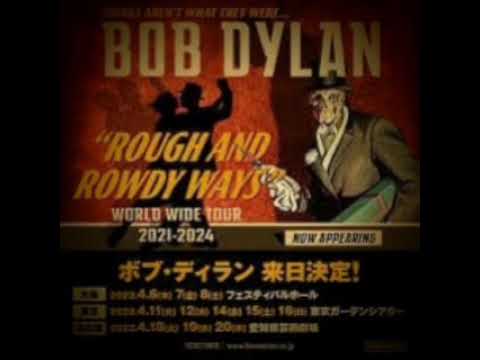

Indeed, I’m relieved to report that this story has a happy ending. Beginning in 2014, Bob Dylan immersed himself in recording and performing material from the Great American Songbook, and when he spoke about these songs at length (to Robert Love in 2015 and Bill Flanagan in 2017) it was clear that his passion for the songwriting craft remained undimmed. Re-familiarising himself writers like George Gershwin, Gus Khan and Hoagy Carmichael paved the way for Dylan’s own return to songwriting after an eight-year hiatus, and his new album Rough & Rowdy Ways was released in June 2020.

Although there’s still some borrowing on Rough and Rowdy Ways, no one has (so far, at least) unearthed appropriation on the scale of Dylan’s previous 21st Century albums. For his part, Dylan’s comments about the writing of his new songs are the polar opposite of his despondent remarks to Ed Bradley in 2004. As he happily reported to Douglas Brinkley in a New York Times interview (in reference to the song ‘I Contain Multitudes’):

Other phrases jump out: lines like “My eyes are filled with tears, my lips are dry”, “my mule is sick, my horse is blind” and “They will tear your mind away from contemplation” hint at writer’s block, while “Carryin’ a dead man’s shield” and “There’s no one here, the gardener is gone” almost sound like an admission of imposter syndrome. And then there’s the song’s eerie refrain: “Ain’t talkin’, just walking”. Maybe that’s what Bob felt he was doing at this point in time, traversing the globe on his Never Ending Tour but unable to connect with his muse in the way he once had. It’s a desperately sad song, but the closing major chord, which ends the minor-key song on an unexpectedly upbeat note, perhaps offered a sign that all was not lost.

Indeed, I’m relieved to report that this story has a happy ending. Beginning in 2014, Bob Dylan immersed himself in recording and performing material from the Great American Songbook, and when he spoke about these songs at length (to Robert Love in 2015 and Bill Flanagan in 2017) it was clear that his passion for the songwriting craft remained undimmed. Re-familiarising himself writers like George Gershwin, Gus Khan and Hoagy Carmichael paved the way for Dylan’s own return to songwriting after an eight-year hiatus, and his new album Rough & Rowdy Ways was released in June 2020.

Although there’s still some borrowing on Rough and Rowdy Ways, no one has (so far, at least) unearthed appropriation on the scale of Dylan’s previous 21st Century albums. For his part, Dylan’s comments about the writing of his new songs are the polar opposite of his despondent remarks to Ed Bradley in 2004. As he happily reported to Douglas Brinkley in a New York Times interview (in reference to the song ‘I Contain Multitudes’):

“I didn’t really have to grapple much. It’s the kind of thing where you pile up stream-of-consciousness verses and then leave it alone and come pull things out. In that particular song, the last few verses came first. So that’s where the song was going all along. Obviously, the catalyst for the song is the title line. It’s one of those where you write it on instinct. Kind of in a trance state. Most of my recent songs are like that. The lyrics are the real thing, tangible, they’re not metaphors. The songs seem to know themselves and they know that I can sing them, vocally and rhythmically. They kind of write themselves and count on me to sing them.”

It’s always worth taking what Dylan says with at least a grain of salt, but I believe him – he sounds excited, almost giddy, describing the process behind his new material. As Leonard Cohen said, going “for the long haul” takes hard work and perseverance, and is probably a grind a lot of the time. When inspiration pays an unexpected visit, however, it must feel like it's all worthwhile.

This post was inspired by Peter McQuitty's amazing essay 'Dylan at the mercy of the Muse: Girl from the Red River Shore and Mother of Muses'

Hi. I really enjoyed what you wrote here. how things just come out, and then how there might be silence. Maugham probably experienced that. in bob's case, i think using things from other sources helped his own creative process. stimulated him. because it all must have become kind of boring after a while. and let's face it, most of all the people working in his genre are pretty lame. I remember when some news magazine called Bruce Springsteen the new Bob Dylan. Years later, I'm still laughing. I mean really lame. As for Bob being a thief, he let his critics shit on the carpet and then revealed for some things he had actually already paid for the right to use some verses etc. As an astute business man would do. In one speech he called them, "pussies and wussies" as we would back in the 9th grade. Something good to describe CNN etc. Yeah, pussies and wussies. But in bob's case, as time goes by, you have to look into other art and not just your own experiences at 20 or so. Or collaborating. With, for example, Levy. It was OK, their stuff. But for a few songs only. Bob knew that had limitations. I met Dylan in 89 and talked with him alone. I asked him if he listened to "serious" music. He said, "like operas and stuff?" I said, yeah. He said, sometimes. I was hinting at Dvorak and others in music who were incorporating folk melodies, not that Bob's music wasn't serious. Most of us probably don't even know that Dvorak and Tchaikovsky and Shostakovitch had visited USA or that they used folk melodies. You write around those things you incorporate after a time. In your music or in your lyrics. in both in bob's case. I mean, he is diverse in melody, and he is diverse in lyrics. Of course he uses old blues melodies; everyone does. Those Muddy Waters and earlier melodies are actually folk music, Slave music, church music. But Dylan also creates melodies. As for lyrics you need to make references after a while or you just keep repeating great songs, and no matter how great they are, they only go so far. "I Want You" or "Lay Lady Lay". etc. But one of Dylan's most profound lines is in Lay Lady Lay: whatever colors you have in your mind; I show them to you and you see them shine. That kind of sums up what art does to our minds, it summons something. Good art and bad art can be measured on how much it stimulates in your mind. "Piss Christ" or "1 Corinthians 13" could be examples. One leaves you with nothing and the latter gives you something to really chew on after the initial reaction. For years in your life. And beyond. I think Bob just tries to have some fun with words and melodies. He is stuck in a genre of stupid and boring people who obviously know little of folk melodies or literature. Bob asked me what I did. He approached me. saw me standing there looking at him. "hey man, what do you do?" I told him I was bored after grad school trying to find a job. He was quick to respond, "Everything's boring." His genre is boring. He's brought life to it but there have been no new Bob Dylans. It is a genre that is limping along and survives because a few guys like Bob and Cohen took the time to give life to something. Bob can grab a few references from history or literature. Cohen some from bible. I think before we jump on the clown car of finger pointing, we realize that such guys always have utilized what came before. I think it's in Ecclesiastes that says, There is nothing new under the sun. I enjoyed your writing. Sorry I went on for so long. JD

ReplyDeleteThanks JD! And no need to apologise, your comment was really interesting.

ReplyDeleteHi Tim. good hearing from you.

Deletethe downside was I had wanted to show Bob where Hoagie Carmichael wrote "Stardust" and Hoagie's grave a few blocks away. "Stardust" is one of the most famous pop songs of all time. And across the street from where he wrote that song, he graduated from I.U. Law School. I lived on that same block for 5 years. Bob was there to do his part for a video for "Political World." I overheard someone at the Law School say he was going to be there doing that so I pursued it. If you watch the vid, those people were filmed somewhere else, L.A. probably. Bob's part was just grafted in. He wore that bad big blue t shirt the whole day. No make up. Nothing. Like he just rolled out of bed. But we didn't get to talk Carmichael which he would have loved. We shook hands though, and he was real nice. I wish I had a photo of us standing alone. Hardly no one knows where he made that part of the video. it was I.U. Bloomington campus on 21 Nov I think. Check it out. Tks, john

That's really cool! Not many people can say they've had a one-on-one talk with Bob Dylan. Very interesting details on the Political World video, too, and Hoagie Carmichael.

Deletebriefly, a lot more people meet and chat with Dylan than you think. by chance. he's out and about. but you TRY to schedule a meeting, well, good luck. I've been around him a couple times. he's Robert Zimmerman then and not Dylan. Dylan is largely an act. but my thing was just serendipity. Yeah, He'd love to see Hoagie's grave. But Mellencamp flunkies directing his movement. so I just left and gave up on that. Take care.

Delete